Will and William West conundrum: How two unrelated but identical inmates showed need for fingerprinting

.

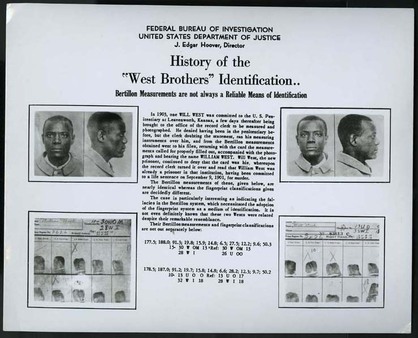

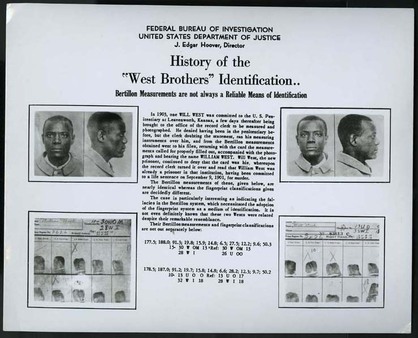

The history of fingerprinting criminals starts with a man named Will West, convicted of a minor crime, who in 1903, upon arrival at the Leavenworth Penitentiary in northeast Kansas, was informed that he was already in prison serving a life sentence for first-degree murder. Well, sort of, for he was checked by the Bertillon identification system in the prison and his face matched completely with that of another William West who was in their criminal database and behind bars in that same prison.

Same name and strangely enough almost identical facial features, but to much surprise to prison officials, two completely different individuals.

Two years prior, in 1901, a convicted criminal named William West was received at the United States Penitentiary in Leavenworth, and in what counted as a formal procedure, M.W. McClaughry, the records clerk, took his Bertillon measurements, compiled an archive file for the inmate, and informed him about the rules in the prison as well as the number of his cell.

The Bertillon system for criminal identification was a technique developed by the French handwriting expert, dedicated criminologist, and biometrics researcher Alphonse Bertillon, and from 1887 was implemented throughout the United States penitentiaries so that they could keep detailed report cards for the inmates. It was nothing more than a simple criminal mug shot, only with a detailed description of the person’s face attached to it.

It worked just fine like this, as criminals were identified by their picture and their full name only, or for a short while at least. It took no more than two decades for a person to emerge that bore a striking resemblance to another, despite the unlikeliness of such an occurrence, and, uncannily, in the same prison, and having the same name to boot.

The Bertillon system for criminal identification was a technique developed by the French handwriting expert, dedicated criminologist, and biometrics researcher Alphonse Bertillon, and from 1887 was implemented throughout the United States penitentiaries so that they could keep detailed report cards for the inmates. It was nothing more than a simple criminal mug shot, only with a detailed description of the person’s face attached to it.

It worked just fine like this, as criminals were identified by their picture and their full name only, or for a short while at least. It took no more than two decades for a person to emerge that bore a striking resemblance to another, despite the unlikeliness of such an occurrence, and, uncannily, in the same prison, and having the same name to boot.

That clerk previously mentioned received another convicted felon at his office, sent to Leavenworth to serve his time. He had his picture taken and was measured using the Bertillon system, and as it happened, upon the standardized checkup, a file with the name William West popped up from the prison’s archives. The clerk asked the man, “What now? What have you done now?” Confused, Will, answered that it was his first time in here, and moreover, it was his first ever conviction.

Initially, the clerk was not shocked nor startled, understanding that almost every criminal reluctantly rejects his crimes, and muttered simply “mm hmm” to the man, whilst looking through his file the whole while, when suddenly to his surprise, it turned out the file in front of him belonged to a man still serving his sentence in the prison. Staring at the face in the file, this man had the exact same bone structure, equal nose length, mouth shape, and positioning of the eyes as the person sitting in the chair, across from his desk in front of him.

He ran a double check, and, sure enough, everything was completely identical, as if a clone of the inmate sat before him. Subsequently, to avoid similar confusion in the future, and after hearing that Bertillon had made another breakthrough in the advancement of dactyloscopy by identifying and convicting a murderer based on his fingerprints, the prison adopted this fingerprint identification system instead of the older one, viewing it as a more reliable method for identification. As it turned out, it was very reliable, as the two inmates after being examined in 1905 displayed entirely different patterns.

That clerk previously mentioned received another convicted felon at his office, sent to Leavenworth to serve his time. He had his picture taken and was measured using the Bertillon system, and as it happened, upon the standardized checkup, a file with the name William West popped up from the prison’s archives. The clerk asked the man, “What now? What have you done now?” Confused, Will, answered that it was his first time in here, and moreover, it was his first ever conviction.

Initially, the clerk was not shocked nor startled, understanding that almost every criminal reluctantly rejects his crimes, and muttered simply “mm hmm” to the man, whilst looking through his file the whole while, when suddenly to his surprise, it turned out the file in front of him belonged to a man still serving his sentence in the prison. Staring at the face in the file, this man had the exact same bone structure, equal nose length, mouth shape, and positioning of the eyes as the person sitting in the chair, across from his desk in front of him.

He ran a double check, and, sure enough, everything was completely identical, as if a clone of the inmate sat before him. Subsequently, to avoid similar confusion in the future, and after hearing that Bertillon had made another breakthrough in the advancement of dactyloscopy by identifying and convicting a murderer based on his fingerprints, the prison adopted this fingerprint identification system instead of the older one, viewing it as a more reliable method for identification. As it turned out, it was very reliable, as the two inmates after being examined in 1905 displayed entirely different patterns.

The story has been retold countless times and is now considered a classic in the field. However, a few versions of it were blown out to such an extent that some even suggested that after checking both of the men’s fingerprints, it was discovered that the second Will, received for a minor crime, was, in fact, the real murderer and not the one already imprisoned. Then again, the authors of this story misspelled the name of the clerk and confused him with his father, the warden at the Leavenworth penitentiary, throughout the event. So as compelling as this story may be, the credibility of the claim is highly questionable.

The story has been retold countless times and is now considered a classic in the field. However, a few versions of it were blown out to such an extent that some even suggested that after checking both of the men’s fingerprints, it was discovered that the second Will, received for a minor crime, was, in fact, the real murderer and not the one already imprisoned. Then again, the authors of this story misspelled the name of the clerk and confused him with his father, the warden at the Leavenworth penitentiary, throughout the event. So as compelling as this story may be, the credibility of the claim is highly questionable.

]]>

Will and William West. Author Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth, “Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living or Dead.” Boston: Gorham, 1918, 31

That clerk previously mentioned received another convicted felon at his office, sent to Leavenworth to serve his time. He had his picture taken and was measured using the Bertillon system, and as it happened, upon the standardized checkup, a file with the name William West popped up from the prison’s archives. The clerk asked the man, “What now? What have you done now?” Confused, Will, answered that it was his first time in here, and moreover, it was his first ever conviction.

That clerk previously mentioned received another convicted felon at his office, sent to Leavenworth to serve his time. He had his picture taken and was measured using the Bertillon system, and as it happened, upon the standardized checkup, a file with the name William West popped up from the prison’s archives. The clerk asked the man, “What now? What have you done now?” Confused, Will, answered that it was his first time in here, and moreover, it was his first ever conviction.

Women clerical employees of the Los Angeles Police Department being fingerprinted and photographed in 1928.